This is a guest post by Nick Grealy.

Nick Grealy has been the natural gas industry for 24 years and found the first 16 really, really, boring. He sees a role for all energy sources except for coal everywhere. He prefers to produce lower carbon energy, not scenarios and would like to make natural gas boring again. Find him at www.ReImagineGas.com and follow @ReImagineGas

The views express here are Nick’s and not necessarily of MyGridGB.

One could simply jump to the end of this post to get the point: The lowest carbon natural gas is inarguably the nearest natural gas. If the UK continues to use natural gas, as it undoubtedly will for at least the next 15 years in generation and longer in heat, why choose to use high carbon natural gas?

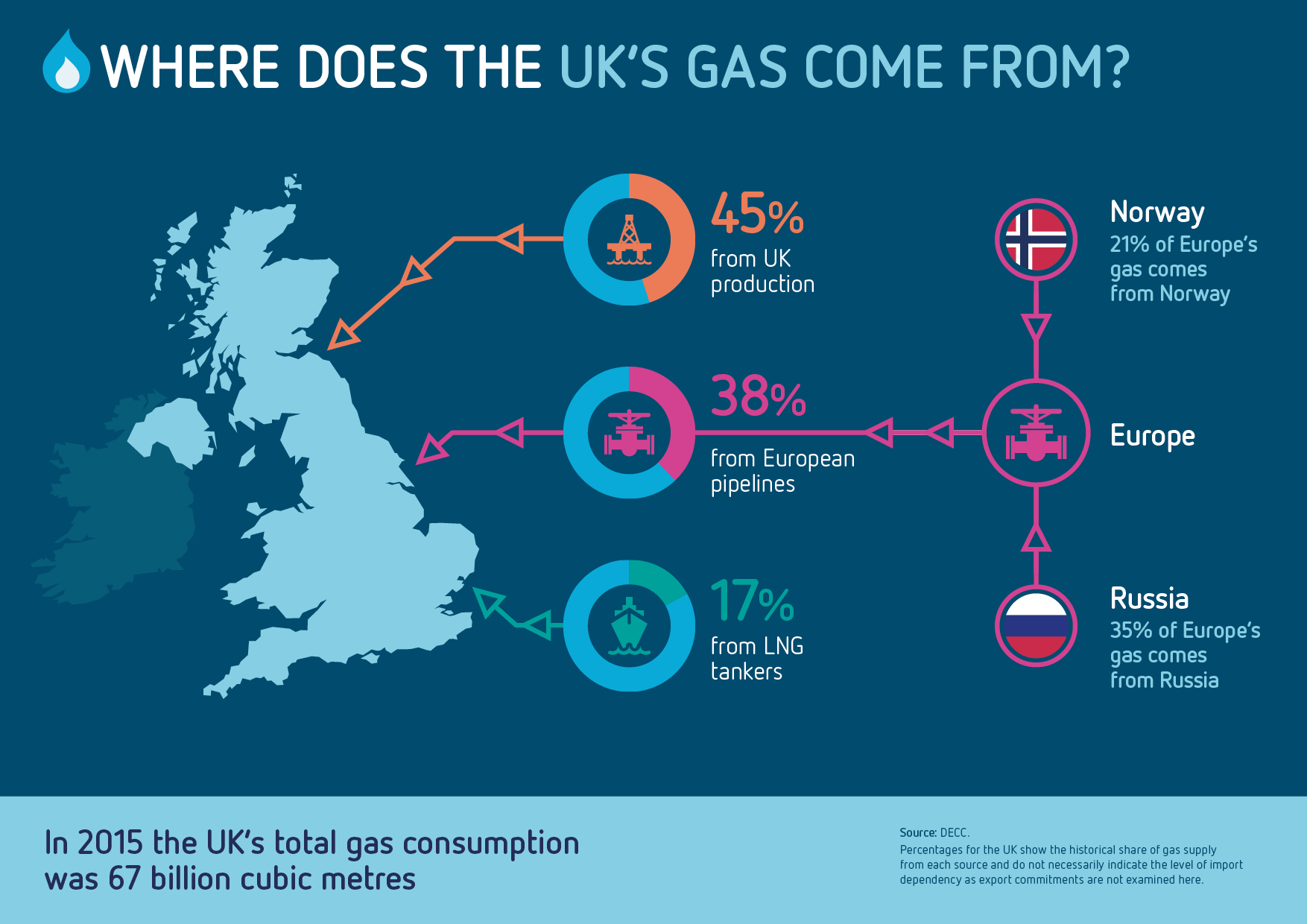

The carbon intensity (CI) of UK electricity generation has been studied relentlessly, but little is known about the CI of natural gas. Much of this is due to both the physical nature of gas and how the provenance of UK natural gas is hard to define at any one point in time in a dynamic, constantly evolving marketplace. This from British Gas should be updated to 2016 figures of 79 BCM, mostly due to gas replacing coal, but the trends remain broadly true:

Unlike electricity, gas doesn’t instantly respond to demand. The gas network has to be in physical balance, but there are plenty of balancing tools that give the operator and markets ways to respond. In the unlikely prospect of every UK power station shutting down at the same time, the result would be almost instantaneous black outs, with only a few emergency generators switching over immediately to run hospitals, police, server farms, telephone exchanges and so on, albeit for only hours or days until the diesel fuel ran out.

If the same happened to the dozen or so gas system entry points, the effects could be weeks away since there is always significant “linepack” in the pipes themselves. Linepack can be modulated up and down within significant ranges and is the reason why old style gasometers have disappeared from the landscape. Further gas is in storage but a six week cold spell would empty it, putting the UK at the mercy of LNG markets. LNG markets have many drivers that will most likely deliver gas, but at both a high financial and CI cost if other global events align.

There is no monolithic driver on UK gas supply. Gas supply, and thus price, depends on many drivers and they constantly change. At the same time, the actual carbon intensity of the UK grid depends on where gas comes from and depends more than anything on distance.

There are three evidence based studies on the CO2 footprint of various sources of UK gas supply. David McKay wrote an analysis on shale, and carbon for DECC in 2013. The Sustainable Gas Institute at Imperial College London did another in 2015 which included a study of methane emissions and an EU funded study in progress informs best of all by measuring the well to wheel emissions of various sources of natural gas in natural gas vehicles, again including a range of methane leaks. That study, page ES9, clearly states:

In general, the CI(Carbon Intensity) is high in gas streams related to long pipelines and/or long distances of transport in the form of LNG, and/or high methane fugitive emissions

The EU figures would be essentially the same for emissions from well to burner tip, either in heating or gas fired generation. The study compares the carbon intensity of natural gas delivered to various locations in Northern and Southern Europe from Russia, Algeria, Qatar LNG and from the Netherlands onshore. Netherlands onshore has the lowest CI and the UK CI reflects the mix of 2015

CI: Carbon intensity grCO2eq/MJ

- Netherlands Onshore

- 6.57

- UK (North Sea, Norway and LNG)

- 11.45

- Qatar LNG

- 23.87

- Russia (to North West Europe)

- 28.77

There is a proven way to cut the CI of UK natural gas and the electricity generated from natural gas. It’s not one some might like, but it’s inarguable. The solution is to use the closest natural gas, that which may be under our feet – if we are allowed to even explore for it. Assuming the same footprint as Netherlands Onshore, the CI of UK gas supply would drop 4.88 gr CO2 per MJ or 42%. The Committee on Climate Change sees a need to cut 74% from all carbon in the 2013/2050 period. This should be a fundamental attraction for any science based environmentalist. Sadly, we have suffered from a debate based on feelings, not facts.

Opposition to UK onshore gas demonstrably causes a perverse outcome to what green opponents say is vital for the planet and on which I agree: cutting CO2 is imperative.

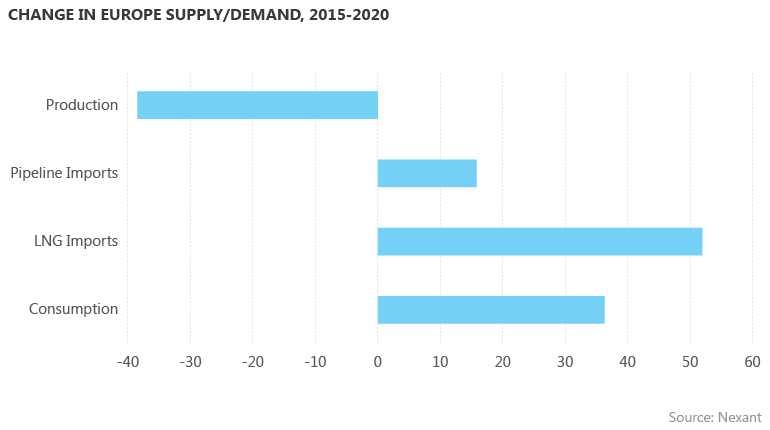

On a global scale the results are also the antithesis of what those who fight climate change and inequality say they are trying to achieve. If the UK doesn’t buy LNG for example, the price will fall for others, making the transition to a lower carbon world easier for emerging economies. But if the UK competes on price with less rich countries, they are condemned to either no power at all or a coal based future. That is the clear choice. Choices have consequences. This from Nexant gives a helicopter view of EU gas demand – and supply – to 2020.

UK natural gas comes from several sources. The nearest to London and most of England comes from the original North Sea discoveries in the Southern North Sea. Here, ’dry’ gas is declining, despite some recent stanching of production declines. Ironically, much of recent increases comes from hydraulic fracturing which has been used 17 times off shore since 2011. The Northern North Sea, between Scotland and Norway is also declining but at a lower rate reflecting a later start in the 1980’s and 1990’s. That gas is associated or ‘wet’ gas produced from wells alongside greater volumes of oil. It is rare for hydrocarbon wells to be either entirely gas or entirely oil, there’s always at least some of each. Producers can’t leave either one in the ground – they are a package deal.

Offshore oil made sense in the ‘peak oil’ era when oil was over $100 a barrel, but now it’s both expensive and naturally has a higher CI from emissions embedded in the chain. For just one example, the 140 or so well pads in the North Sea need up to 2 million helicopter passenger movements each year. Platforms at sea need huge amounts of steel and concrete and people and food. They also need a million euro per km for pipeline tie ins. The North Sea is the largest offshore province in the world, but cheap oil from US oil wells using shale techniques first perfected in gas production, make it one of the most expensive areas today. As a result, the high cost of North Sea oil does not bode well for UK gas production. The peak of North Sea gas was reached in 2001 when there was enough UK gas available for export. But the writing on the wall was there even in the 1990’s when the first LNG import terminals were planned.

But the other alternative, Norwegian gas is also declining. We can envisage how in the 2020’s and beyond Norwegian gas, the other main supplier to both the UK and Europe, will decline for three key reasons. One is geological, but the other two are political. Norway’s economy is founded on oil and gas, but with huge hydro power reserves, Norway (which ironically doesn’t have any domestic gas heat demand itself) is facing pressure to disinvest from oil and is moving aggressively to decarbonise transport via electric vehicles. EV’s are a transition they can well afford as their sovereign wealth fund recently reached a trillion dollars, divided among just over five million people. Norway has two choices: go green or continue to produce oil but from waters in the Barents Sea in the Arctic Ocean. Norway can afford to go green, but can the rest of Europe? The rest of Europe sees Norway as a balance to Russia, and Norway, sharing a land border with Russia, will find life further complicated by Brexit. If it’s the UK or Europe, Norway will naturally pivot to their strong connections to Europe.

Thus another irony of climate based opposition is that foregoing UK onshore gas could lead to it being replaced by Arctic drilling, yet another perverse outcome alongside higher local and global CO2. Another own goal would be greater world poverty and 5 million deaths per year from indoor cooking fuel. (Collecting bio mass instead of affordable cooking gas also ensures more girls destroy their local environment by cutting wood, and even worse, destroy their own lives better spent in school).

Norway is a strong partner of the EU without being in it. The Norwegian EFTA membership is their compromise with Europe, and in the event of a hard Brexit with the UK, or what remains of it, outside of the EFTA area, Norway may not even have any incentive to continue, let alone increase, oil and gas exports to the UK, especially one minus Scotland.

Pipeline and offshore natural gas transmission systems are powered by jet engine based compressors which maintain the pressure needed to keep the system moving. Compression needs system gas as fuel. The longer the pipeline the higher the CI since compressors are placed 70 KM or so apart. Longer pipelines also increase the chance of leaks of methane. UK onshore gas to pipeline distance is trivial, and the UK National Grid system is one of the best in the world for leak detection and repair. Even if other pipelines such as the 6000 KM distances from Russia, or 5,000KM from Azerbaijan or southern Algeria are as reliable as ours, distance equals an increased risk of leaks.

Compressors from Russia alone are equal to the CO2 footprint of 85 jet engines running 24 hours a day, or several dozen of the short range flights Heathrow opponents oppose on climate grounds. Compressors are also abundant in the UK offshore, with most gas coming through the St Fergus gas terminal in Scotland, 400 to 600 miles away from the majority of demand, sent by compressors to England.

The choices measured in CI are thus local, UK onshore, Norway onshore and European imports, The next import choice is increasingly the most abundant, yet at the same time one often with the highest CI of all – LNG.

Onshore gas naturally has minimal compression needs. Coming out of the ground from 2000 meters depth, the pressure is already strong enough that gas needs to be constrained, not compressed.

The North Sea and Norway currently provide about 70% of gas supply between them, but natural declines in both sectors will see a rapid decline over next few years. 30% today comes from LNG imports or pipeline imports from Europe. Since the rest of Europe also has little domestic production, most of those molecules come either the long way around from Norway or the even longer route of 6000 KM from the main Russian gas fields. Russia provides 40% of EU consumption in 2017 and any gas imported by the UK depends on it as a large component. We also have the ongoing complications in the onshore Netherlands where the Groningen gas field is also declining.

That leaves the UK, and Europe, dependent on LNG, gas which is produced often at some distance from shoreline terminals, and then processed and frozen to 162 °C , at which point it becomes a liquid and takes up 600 times less space than pipeline gas. EU LNG’s CI comes via carbon produced in the gas field, then expended transporting it to the terminal, more again to liquefy it, then to transport it and then to reheat it at the receiving terminal. All of these processes except the last happen outside of European regulation, which is only concerned with the gas quality once it leaves the terminal

LNG trading is incredibly complex and prices depend on multiple variables which may not make sense to local consumers. LNG prices for example have had recent spikes due to increased Japanese LNG demand after Fukushima but also due to droughts in Brazil causing sudden imports of LNG for generation to replace hydro. Weather is always a key driver and 2017 produced the seeming contradiction this mild UK winter, of rising prices due to cold snaps in China and Korea. Long LNG supply chains also carry geopolitical risk especially in key choke points in the Persian Gulf, Red Sea and Strait of Malacca.

We are currently in the early stages of a global gas glut of LNG. Around the turn of the century, considerations of short supplies of LNG led to the financing and construction of several LNG export projects, the largest being in Australia. Several smaller projects in West Africa, Peru and Papua New Guinea joined the existing gas to LNG projects created in Indonesia, Brunei and Malaysia that had targeted Japanese gas consumption since the 1970’s.

Australian projects were incredibly expensive, with the Gladstone project dwarfing even Hinckley Point at $50 billion. From the perspective of 2005, such projects were considered profitable but today they find themselves up against US LNG exports. The US had the good fortune to have existing LNG import terminals that could be quickly retooled to export mode to take advantage of the huge resources released by the original shale boom in Texas and elsewhere.

The basic CI of LNG depends on distance, but the distances travelled don’t follow consistent – or often logical – paths. In March 2017 we had the unprecedented case of a Peruvian LNG cargo imported to the UK, the voyage alone taking four weeks. It will amaze consumers, but not traders, to learn that we will probably see Australian cargoes reaching the UK this decade. We will inevitably see the arrival of US LNG. This will be particularly ironic for the protestors outside UK shale sites who often have signs saying “No Shale Gas Anywhere”, who will at least be able to cut their footprint by arranging a picket line no further away than their own central heating boiler.

Using the EU study, it’s possible to extrapolate the CI of US LNG along the entire supply chain. US LNG comes for now from the Gulf of Mexico, but contracts are in place to source the gas from Pennsylvania and even Alberta. Alberta gas will have a Russia to Europe distance even before the gas is loaded.

Using the Qatari and Russian pipeline figures, we can see that using US shale gas instead of our own gives some very alarming figures:

US LNG (Alberta)

38.56

US LNG at terminal

19.0

US LNG Pennsylvania

30.5.

When US LNG from Maryland arrives, perhaps as soon as Christmas 2017, it should have a relatively low CI, perhaps as low as 10 or 11, but still double that of onshore UK shale gas.

Finally, this comes back to morality. Most of the opponents of UK shale saw the Gasland movie, which alerted the world in 2009 to the “danger” of “extreme” Pennsylvania shale gas drilling. No matter that in 2017, Pennsylvania’s production has increased from 5 Billion Cubic Meters a year in 2008 to over 210. Pennsylvania and Ohio now produce more gas than anywhere except Russia. This has happened with none of the dangers and a declining amount of countryside impact, with only 27 rigs in the entire state as of last week. It’s also happened in a country with the most lawyers on earth. If there has been provable damage, US tort lawyers would have monetised it long ago.For those who see the a cover up, the bucks of damages don’t stop at Lloyds of London either. Willis Watson, the second largest reinsurer in the world have not paid out a penny. Extrapolating 2017 Pennsylvania rig figures to the UK, instead of 2009’s, we see that we could replace the entire 14 BCM of LNG to UK imports with perhaps as little as half a dozen rigs at peak.

Do we choose to displace our heat demand onto the backs of rural Pennsylvanian, enriching multi national LNG trading houses and causing, not curing, increased climate change for the selfish reason of not causing a handful of UK resident’s alarm?

Morality is also tied to money. UK gas and oil resources are the property of the Crown, i.e. all 65 million (for now) of us – not the caricatures of evil gas companies presented in Greenpeace or Friends of the Earth demonstrations. The tax take will be approximately 40% for the Crown, and individual gas well pads could pay business rates of several million pounds each per year. The Peru cargo mentioned above had a value of roughly £12 million pounds alone. In sailed several million extra tons of CO2, but then out sailed £5 million which could have stayed home insulating 1600 homes or hiring 150 teachers or nurses for a year. From one single ship. Is it fair to the 65 million UK gas resource owners that concerns of several hundred at most about a dozen extra trucks a day for three months at peak force the majority to forego the benefits? We need a grown up national conversation, based on national and global climate facts, not only based on the feelings around the legitimate – and addressable – concerns, of local communities alone.